The mendicant orders which appeared at this time, like the Franciscans and Dominicans, put great emphasis on the organisation of teaching and the education of their friars.

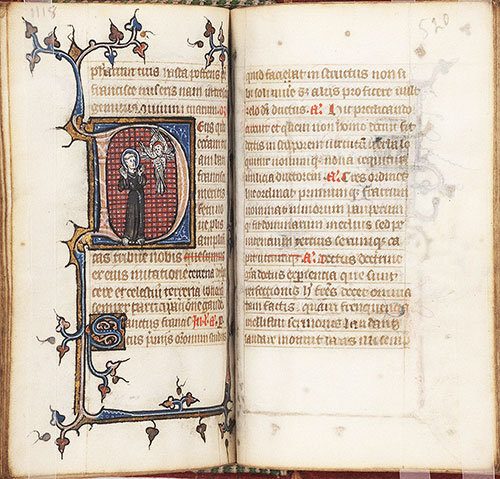

Also within ecclesiastical circles, there were changes to the way spirituality was understood that affected education and the transmission of culture, now no longer produced exclusively within monasteries. These had started out as clusters of schools, generally of lay teachers, or even as groups of students who had banded together to employ teachers. To respond to these new demands, cities facilitated the establishment of universities, centres of learning set up under papal, episcopal, or royal protection. New activities helped to question the Church’s monopoly on cultural education at the same time, the development of the bureaucratic apparatus -both of the Church and of the state- required specialised professionals, especially in the field of law. The process was completed when the manuscript was bound, for which a variety of materials were used, normally leather and wood.Įxamples of writing implements: quills and a reed pen And after the monasteries?įrom the 12th century onwards, economic and social changes caused by the evolution of trade favoured the growth of urban centres and the mobility of laypersons. Later on these tasks were divided up and carried out by different people: the copyist (an expert in calligraphy) left blank spaces for the miniaturist, the illuminator, and the chrysographist (responsible for the gold lettering) according to the level of ornamentation planned for the manuscript. In the early Middle Ages, some copyists were true artists who, in addition to copying the text, also added the various embellishments: the illumination (the application of colour and decoration) and the miniatures (the figures and illustrations) which sometimes accompanied the titles, as well as the rubric, capital letters, borders, vignettes, friezes, etc 2. To make these manuscript copies, monasteries had a room known as a 'scriptorium' where the copyists (also known as scribes or amanuenses) copied from an earlier text or followed the dictation of a reader (which meant they could make as many copies as there were copyists in the scriptorium).

They copied biblical and liturgical texts, as well as works by the Church Fathers, canonical writings, and some secular texts, including works on civil relations law, grammars, glossaries, and Latin texts by Classical authors (like Terence, Virgil, Ovid, etc.) in order to hone their Latin skills.

Benedictine monks incorporated the copying of manuscripts into their regular work, motivated in part by the need to provide the basic texts for the development of their spiritual life.

In the early Middle Ages manuscripts were primarily produced in monasteries cathedral schools were responsible for intellectual instruction -fulfilling the role of the schools of rhetoric of the Roman Empire- a task that monasteries and convents later took over.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)